Geometry, All Around Us

Geometry is all around us, and we are surrounded by myriads of geometric forms, shapes, and patterns. Every living organism and all non-living things have an element of geometry within. Understanding the natural world requires an understanding of geometry.

Where there is a matter, there is geometry. (Johannes Kepler)

For me, geometry is a fascinating subject. As the subject of learning, geometry requires the use of deductive reasoning, a logical process in which a conclusion is based on the multiple premises that are generally assumed to be true (facts, definitions, rules). Learning geometry also develops visualization skills and spatial sense - an intuitive feel for form in space.

Geometry is essential in architecture and engineering fields and mostly used in civil engineering. Thorough knowledge of descriptive geometry is definitely required for civil engineers and helps engineers to design and construct buildings, bridges, tunnels, dams, or highways. It has been, by the way, one of my favourite subjects during my university years.

I use mathematics and geometry almost my whole life. To write about geometry in a way that does not look like a boring lecture is challenging. It is, therefore, my intention to write this post in a manner of a picture book – geometry in words and pictures, because I prefer visualization wherever possible. I shall try to skip formulas, theorems, rules. There will be only a little math.

This piece is a review of some interesting geometric forms, which are particularly impressive to me.

PERFECT FORMS

Necessary Introduction

Polygons (many sides in Greek) are closed plane figures with straight sides. Regular polygons are polygons whose all sides are equal in length. A regular polyhedron (pl. polyhedra) is a three-dimensional solid whose all faces are regular polygons.

Platonic Solids

These regular polyhedra are called the Platonic solids or perfect solids, named after the Greek philosopher Plato although he is not the first who described all of these forms.

The Platonic solids are symmetrical geometric structures, bounded by regular polygons all of the same size and shape. Moreover, all edges of each polygon are the same length and all angles are equal. The same number of faces meets at every vertex (corner or point).

Furthermore, if you draw a straight line between any two points (vertices) in any Platonic solid, this piece of the straight line will be completely contained within the solid, which is the property of a convex polyhedron.

An amazing fact is that can be only five different regular convex polyhedra. These perfect forms are:

- Tetrahedron

- Octahedron

- Hexahedron (cube)

- Icosahedron

- Dodecahedron

![_- PLATONIC SOLIDS ~~.

TETRAHEDRON OCTAHEDRON HEXAHEDRON ICOSAHEDRON DODECAHEDRON

. FOUR SIDED EIGHT SIDED SIX SIDED TWENTY SIDED “TWELVE SIDED’

vAHRE ©, -* “AAIR VEARTH ~~ VWATER GAETHER

4 FACES 8 FACES 6 FACES K PARI Ye 12 FACES

4 POINTS 6 POINTS 8 POINTS 12 POINTS 20 POINTS

6 EDGES - * 12 EDGES 12 EDGES .~ 30 EDGES 30 EDGES |

A A A

a] 180°x 8 360°x6 . 18°X20 rer]

720° DEGREES ~~ 1440° DEGREES 2160° DEGREES 3600° DEGREES 6480° DEGREES](https://contents.bebee.com/users/id/11435732/article/geometry-all-around-us/1eez4.jpeg)

Plato was deeply impressed by these forms and in one of his dialogues Timaeus, he expounded a "theory of everything" based explicitly on these five solids. Plato concluded that they must be the fundamental building blocks—the atoms—of nature and he made a connection between five polyhedra and four essential (classical) elements of the universe; tetrahedron → fire, cube → earth, octahedron → air, icosahedron → water, and the dodecahedron with its twelve pentagons was associated with the heavens and the twelve constellations.

Later, Aristotle, who had been Plato's student, introduced a new element to the system of the four classical elements. He classified aether as the “fifth element” (the quintessence). He postulated that the stars (cosmos itself) must be made of the heavenly substance, thus aether. Consequently, ether was assigned to the remaining solid --dodecahedron.

Why Only Five?

Geometric argument and deductive reasoning

Postulates:

- At least three faces must meet at each vertex to form a polyhedron.

- The sum of internal angles of polygons that meet at each vertex must be less than 360 degrees (at 360° they form the plane, i.e. the shape flattens out).

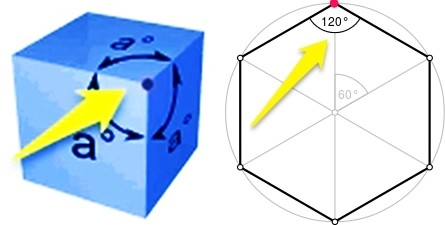

If solid's faces that meet at each vertex are regular triangles, squares, and pentagons, the sum of angles at each corner is less than 360°. Forming a regular solid of hexagons won’t work because hexagon has internal angles of 120°, and in the case where a minimum of 3 hexagonal faces meet at one vertex it gives → 3×120°=360°, thus the shape flattens out.

Consequently, there is no platonic solid formed from hexagons or any regular polygon of more than 5 sides.

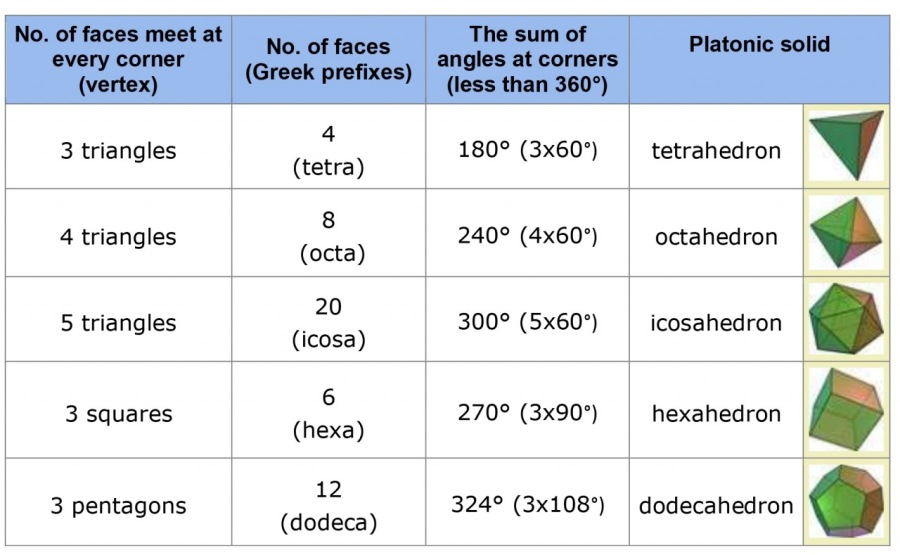

The table below is a result based on previous arguments and reasoning. Solids are made only of regular triangles, squares, and pentagons. There are only five possibilities, thus five regular solids. Any other combination is not possible!

The mathematical proof given by Euler's formula confirmed that there are exactly five Platonic solids.

THE BEAUTY OF PLATONIC SOLIDS' GEOMETRY

Spheres and Platonic Solids

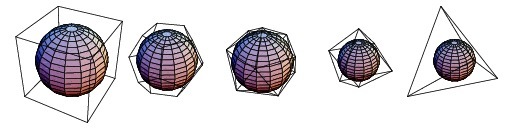

Each solid will fit perfectly inside of a sphere → circumsphere and all the angular points (vertices) are touching the edges of the sphere with no overlaps. Nonetheless, the inscribed sphere → insphere touches all the faces.

Nested Platonic Solids

Platonic solids have the ability to nest one within the other. The corners of the inner Platonic solid touch the vertices or the edges of the outer solid. The amazing animation below shows the configuration of all five Platonic solids, each fits perfectly inside the other.

The video shows how (transparent) dodecahedron opens to reveal a cube inside, which opens to allow a tetrahedron to come out, then octahedron, which opens to reveal the inner icosahedron. All the Platonic solids are harmoniously nested one inside the other.

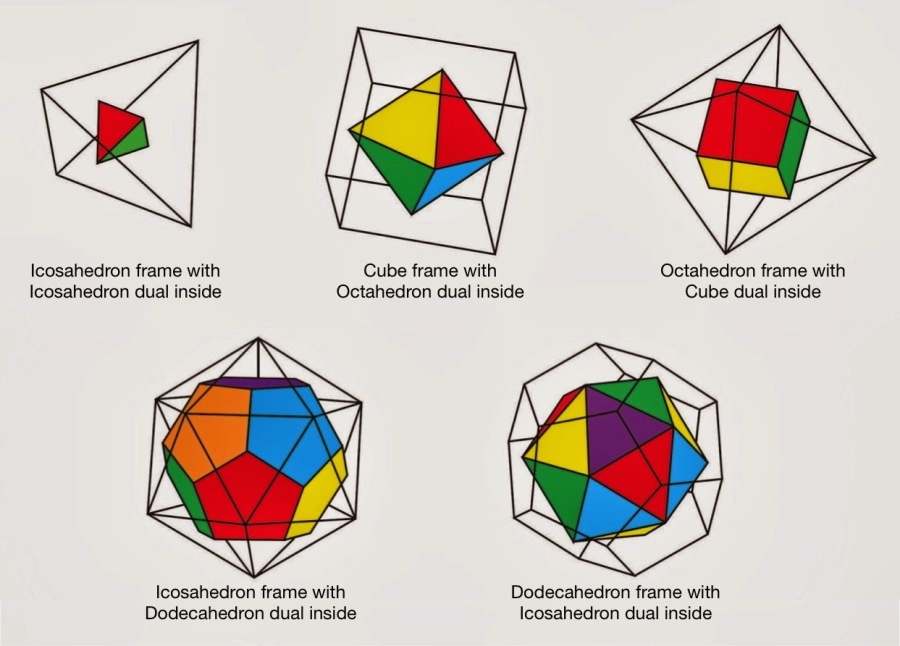

Duals of Platonic Solids

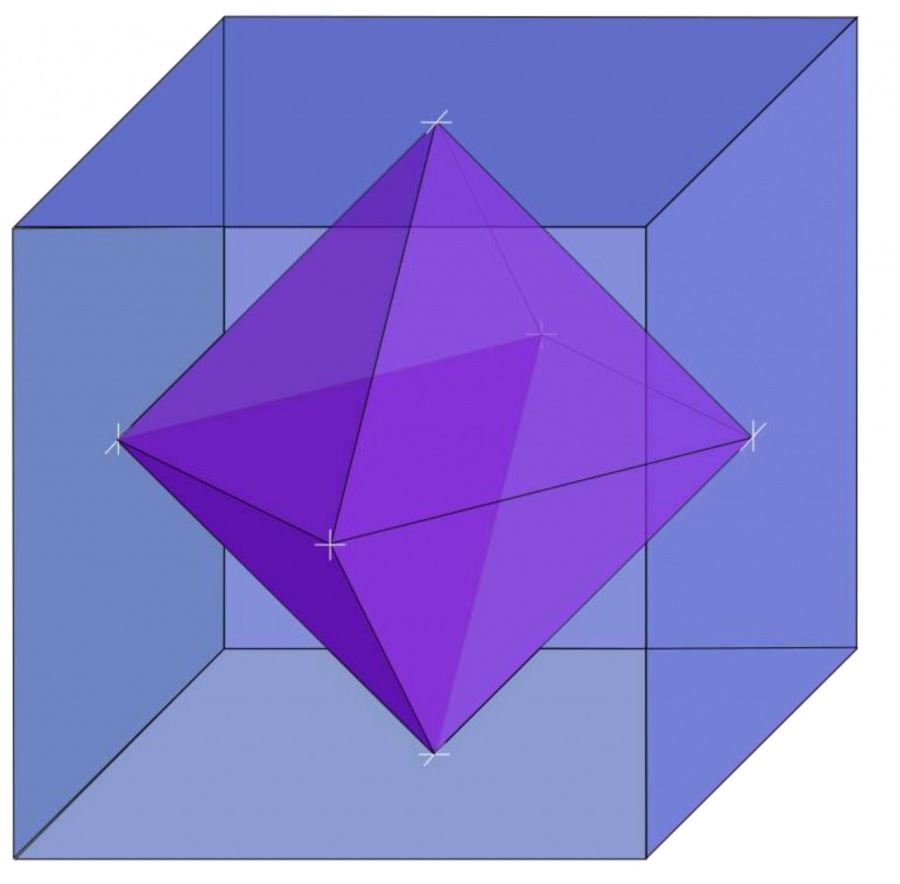

Each Platonic solid has a dual Platonic solid. If a midpoint (centre) of each face in the platonic solid is joined to the midpoint of each adjacent face, another platonic solid is created within the first.

It occurs in pairs between the solids when the number of faces in one solid = the number of vertices in another.

- The tetrahedron is self-dual (its dual is another tetrahedron), the only one with 4 faces and 4 points

- The cube and the octahedron form a dual pair (an octahedron can be formed from the cube, and vice versa), 8 faces in cube=8 points in the octahedron, or 6 points in cube = 6 faces in an octahedron

- The dodecahedron and the icosahedron form a dual pair (a dodecahedron can be formed from an icosahedron, and vice versa), 12 faces in dodecahedron = 12 points in an icosahedron, or 20 points in dodecahedron=20 faces in an icosahedron

The image above clearly shows how the octahedron occurs from the cube - putting a vertex at the midpoint of each face gives the vertices of dual polyhedron – octahedron. In vice versa, by connecting all midpoints of an octahedron’s faces occurs a cube, like in the image below.

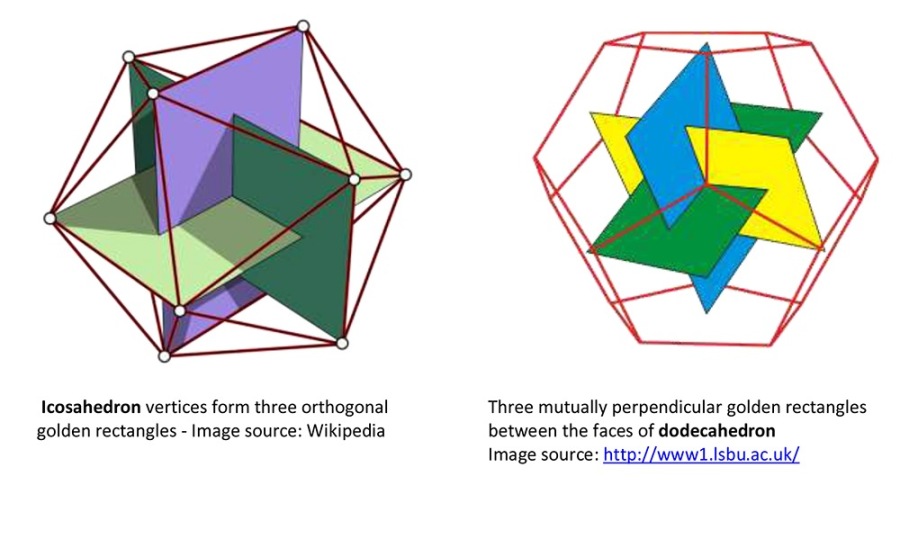

The Golden Ratio in Icosahedron and Dodecahedron

The icosahedron and his dual pair the dodecahedron are uniquely connected with the golden ratio by virtue of three mutually perpendicular golden rectangles which fit into both. These mutually bisecting golden rectangles can be drawn connecting their vertices and mid-points respectively.

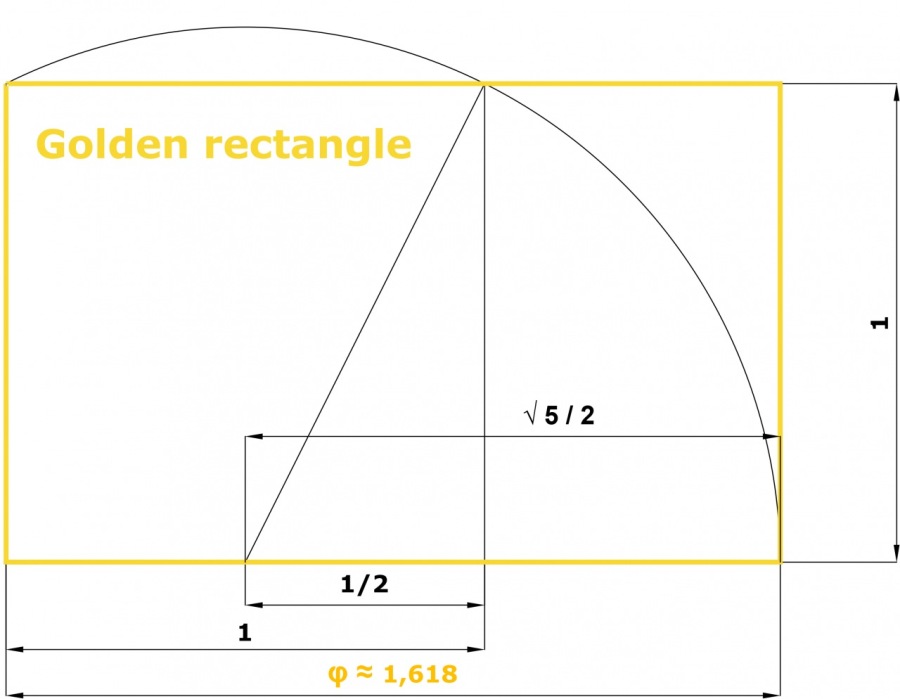

A golden rectangle is a rectangle which side lengths are in the golden ratio, 1: φ (the Greek letter Phi), where φ is approximately 1.618.

Since the ancient days, geometricians have known that there is a special, aesthetically pleasing, rectangle with width 1, length x, and the following property: dividing the original rectangle into a square and new rectangle, as illustrated in the image above, arises a new rectangle which also has sides in the ratio of the original rectangle.

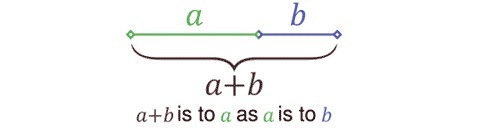

This curious mathematical relationship, widely known as the golden ratio, was first recorded and defined in written form around 300 BC by Euclid, often referred to as the father of geometry, in his major work Elements.

The golden ratio refers to a specific ratio between two numbers which is the same as the ratio of the sum of those numbers to the larger of the two original quantities. The value of the golden ratio is an irrational number, which is 1.6180339887...... (assuming that a is greater than b, and b is greater than zero).

Fractal Structure of Platonic Solids

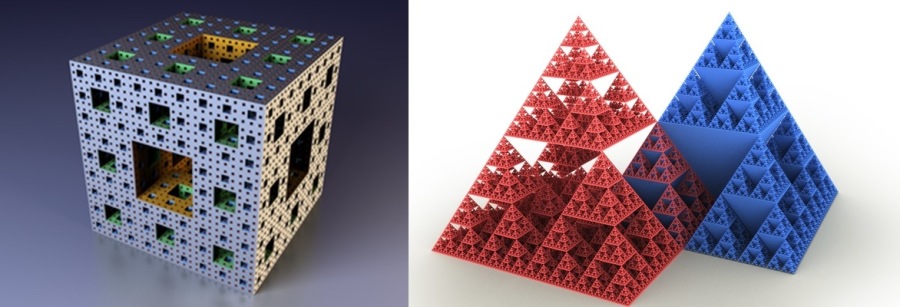

Each Platonic solid has its own fractal structure, the same repetitive patterns that fit within each other. The two famous Platonic fractals are the Menger Sponge for the cube and the Sierpinski tetrahedron for the tetrahedron, a three-dimensional analogue of the Sierpinski triangle, also called the Sierpinski sponge or tetrix.

The illustrations show Menger sponge after the fourth iteration of the construction process, and a Sierpinski square-based pyramid (tetrahedron) and its 'inverse' after the third iteration. On every face, there is a Sierpinski triangle and infinitely many contained within.

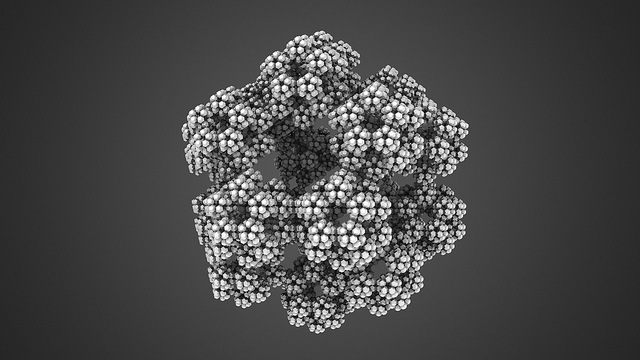

Of all other Platonic fractals, particularly interesting is the Sierpinski dodecahedron. The image below shows a dodecahedral-cornered supercluster, in which a smaller dodecahedron is placed in each corner of the original solid to get a dodecahedral cluster. The process can be repeated indefinitely.

PLATONIC SOLIDS IN NATURE

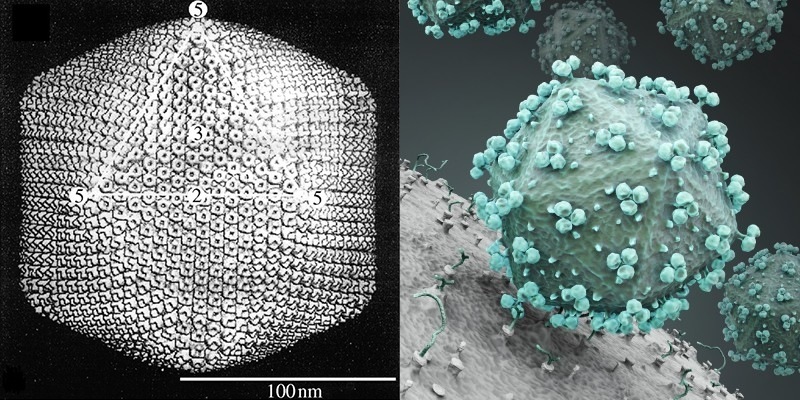

These regular structures are commonly found in nature, but they are generally hidden from our perception. The first manifestation of Platonic solids in nature is in the shape of viruses. Many viruses have a viral capsid, a protein shell that protects and encloses the viral genome, in the shape of an icosahedron. A regular icosahedron is an optimum way of forming a closed shell from identical subunits.

Of all Platonic solids only the tetrahedron, cube, and octahedron occur naturally in crystal structures. The regular icosahedron and dodecahedron are not amongst the crystal habit.

Iron pyrite, known as fool's gold, often form cubic crystals and frequently octahedral forms. Calcium fluoride also crystallizes in cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex forms are not uncommon.

Tetrahedrite gets its name for its common crystal form - tetrahedron. Sphalerite also occurs in a tetrahedral form.

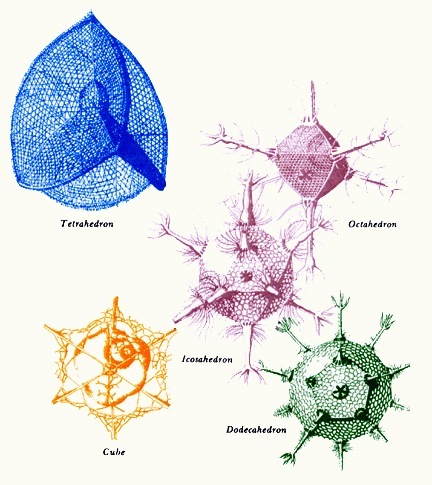

All Platonic solids occur in a tiny organism known as Radiolaria, which are protozoa – single-celled organisms widely distributed throughout the oceans whose mineral skeletons are shaped like various regular solids.

These Platonic forms also emerge in the mitosis of a developing zygote, the first cell of the human body. The first four cells occur by dividing, form a tetrahedron.

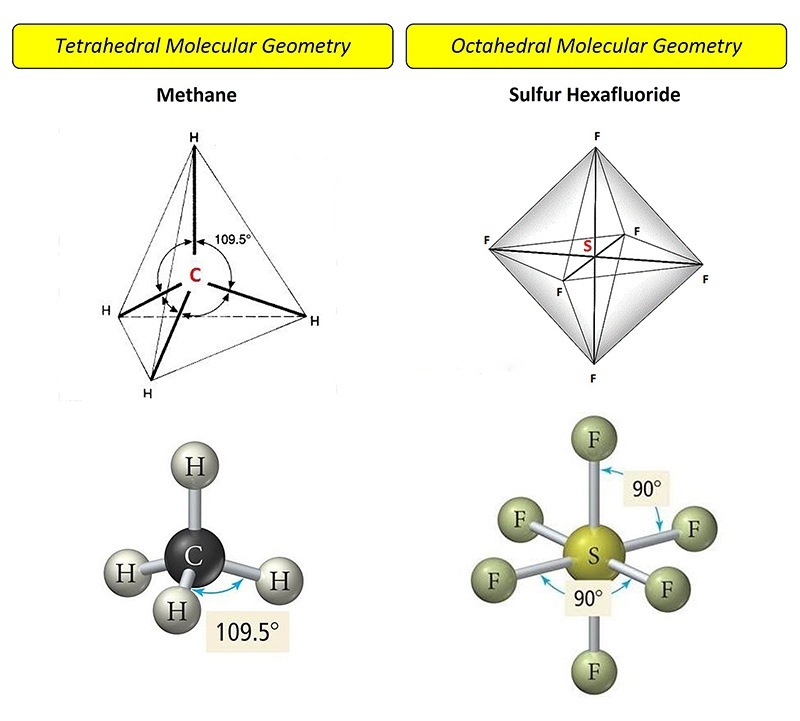

Three-dimensional molecular shapes (molecular geometry)

Molecular geometry is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms within a molecule. Molecules are held together by pairs of electrons shared between atoms known as „bonding pairs“.

A molecule of methane (CH4) is structured with 4 hydrogen atoms (H) at the vertices of a regular tetrahedron bonded to one carbon (C) atom at the centroid. When the central atom has 4 bonding pairs, geometry is tetrahedral. All the angles between the two bonds are about 109,5°.

In a molecule of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) six fluorine atoms (F) are symmetrically arranged around a central sulfur atom and joining together with 6 bonding pairs of electrons and defining the vertices of a regular octahedron. All the bond angles are 90°.

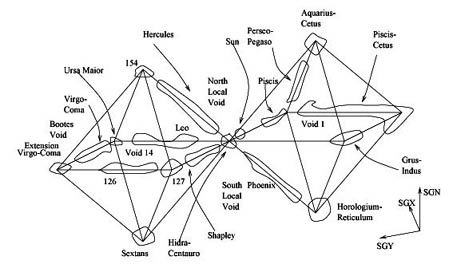

Clustering of the galaxies

Scientific observations made by astrophysics (E. Battaner and E. Florido) have shown that the Platonic solids can also be found in the clustering of galaxies. The distribution of super-clusters presents such a remarkable ordered pattern, like in these octahedron clustering of galaxies in the image below where the identification of real octahedra is so clear and well defined.

There are many more amazing examples showing the occurrence of the Platonic solids in nature.

Above the entrance of the famous Plato's Academy has been engraved a quote of which accurate translation there are still many disputes: "Let no one who cannot think geometrically enter."

On the contrary, I invite you to enter into the world of geometry and comment! Have you ever thought about geometry around us? Do you have favourite forms, shapes or patterns? Do you use geometry in your work?

Sources:

3. https://towardsabetterworld.com

4. Alt.fractals: A Visual Guide to Fractal Geometry and Design

**********

If you like this buzz about geometry, please give it a "relevant" or a comment. If you really like it, please share.

Članci od Lada 🏡 Prkic

Pogledaj blog

An article I read the other day about when we should end a conversation prompted me to put some word ...

When in Rome, do as the Romans do. When in Split, enjoy drinking coffee as the · Splitians · (Split ...

There's no doubt that our mind muscles need constant exercise. Keeping your brain active as long as ...

Vezani profesionalci

Možda će vas zanimati ovi poslovi

-

Senior Product Manager B2B

Pronađeno u: Manatal GBL S2 T2 - prije 1 tjedan

PRAGMATIKE Zagreb, HrvatskaJob Description: · Location: Fully remote, EU timezone (CET +/- 2hours) · Start date: ASAP · Languages: English is mandatory; French is a plus · Our client: Cloud Computing / Blockchain / AI - European Saas · Responsibilities: · Lead the definition and execution of our client's p ...

-

Повар, помощник повара, официанты

Pronađeno u: beBee S2 HR - prije 3 dana

WorkinCroatia Пореч, Hrvatska FreelanceЛегальна робота в Хорватії на березі моря Кухарі €/міс. (чистими) · Піцца-майстори €/міс. (чистими) · Помічники кухаря - 1200€/міс. (Чистими) · Помічники на кухню (мийка посуду, нарізка овочів) - 4€-5€\год. (Чистими) · Помічники офіціанта €/міс (чистими) · Бармени €/міс (чисти ...

-

sap logistic consultant

Pronađeno u: beBee S2 HR - prije 4 dana

Atos Zagreb, HrvatskaThe future is our choice · At Atos, as the global leader in secure and decarbonized digital, our purpose is to help design the future of the information space. Together we bring the diversity of our people's skills and backgrounds to make the right choices with our clients, for o ...

Komentari

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 3 godine #66

Thank you, Debasish!

Debasish Majumder

prije 3 godine #65

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 3 godine #64

Yes it is, Zacharias. Am also amazed by how long this post has remained appealing to readers on both platforms beBee and LinkedIn. It is my favourite post.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 3 godine #63

Thank you, Bill!

Zacharias 🐝 Voulgaris

prije 3 godine #62

Bill Stankiewicz

prije 3 godine #61

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 3 godine #60

Javier Cámara-Rica 🐝🇪🇸

prije 3 godine #59

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 4 godine #58

Zacharias 🐝 Voulgaris

prije 4 godine #57

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #56

Thank you so much, Joanne Gardocki. A comment like this one is the best reason for all the effort and time put into writing the post. :-)

Paul Walters

prije 7 godina #55

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #54

Thank you dear Ali Anani for commenting again. That means a lot, especially coming from such a great thinker.

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #53

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #52

Ginger A Christmas, I am amazed at your comment. You can really think geometrically. 🙂 Many students always ask themselves the same question that you asked, “When am I going to use this in my life?” But you had a very wise teacher whose answer I really liked, “Think further, Miss, think further.“ I will remember this. Thank you for sharing this post on other social media. I've started blogging just recently and don't write as much as I would like. This is the post I like the most.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #51

Thank you Ben. It is one of the best compliments I received on my article. :)

Milos Djukic

prije 7 godina #50

My pleasure Lada Prkic :) Thanks!

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #49

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #48

Glad you like it Margaret. The new post about "human forms" is already taking shape in my mind.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #47

I shall try. Am really intrigued by this idea.

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #46

The greatest love is towards the greatest reality- people. This is why I attempt to use science to explain human-related activities. Please find the time to write your promising buzz Lada Prkic

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #45

Thank you very much! You beautifully compiled other people's thoughts, but your idea is a seed for all these thoughts. :) I'd love to have the time to write a post about shapes and colours of humans. I am just writing another buzz related to geometry, which is obviously my first love.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #44

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #43

Beautiful your comment is dear Lada Prkic as well as your sharing on LI. You add new colors of thinking to the presentation. This presentation is in reality a compilation of beautiful minds.

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #42

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #41

It took me a while to comment on your SlideShare presentation dear Ali Anani, http://www.slideshare.net/hudali15/thinking-shapes-and-colors I tried to contribute in a valuable way. Hope you find it worthy. :-)

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #40

I forgot to thank you for your words of praise, Milos. They make me happy. :-)

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #39

I can't thank you enough for promoting my post here and on Pulse, my dear friend. You have shown me a real meaning of social media engagement.

Milos Djukic

prije 7 godina #38

Yes you did Lada Prkic :) Congrats! A masterpiece in science communication.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #37

Many thanks Franci Eugenia Hoffman. I really tried to make it interesting and informative. It seems I have succeeded.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #36

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #35

The sacred geometry is an extremely fascinating concept. I agree, Savvy, that it takes time to fully comprehend its principles and applications. Thanks for the link about the celestial DNA time spiral. I am just at the beginning of my fractal journey, but I shall try to learn more about this.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #34

Like you said, dear Ali Anani, some posts that move us require repeated reading, and your presentation is one of them. It takes time to absorb all the thoughts based on you great analogy. I’ve just started to read and I’ll comment as soon as possible.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #33

It would be my pleasure if you re-visit my post, like our friend Ali Anani did. Thank you for the share, dear Savvy Raj

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #32

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #31

Dear CityVP Manjit, your words express exactly what I think about the educational system. Mathematics is not boring and geometry is not incomprehensible, just the opposite, but the teaching methods make them uninterested for the pupils. To understand geometry or mathematics is much more than learning by rote, which is usually the case. It requires them to connect to real life and they should be taught through the examples in nature. Thank you for enriching this conversation with your comment, as always, and thanks for your kind words about the buzz.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #30

I’m glad to meet another female engineer on beBee. Thanks for your kind words, Dilma. I was hoping people would be drawn to this topic if explained in a visual way because geometry itself is a very visual subject. I was also hoping there will be some kind of conversation on this topic. It seems to me that most people think about geometry as a difficult subject, but instead we use geometry in everyday life although are unaware of that fact - like cutting the food for example. :-)

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #29

Totally understand you, Dale. Next time will be less links, I promise. 🙂 I am glad you have read even linked articles. This is what I hoped when I wrote this buzz. You are kind of a reader every author can only wish. Thank you for that.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #28

I’m glad to meet another female engineer on beBee. Thanks for the kind words Dilma. I was hoping people would be drawn to this topic if explained in a visual way, because geometry itself is a very visual subject. I was also hoping some kind of conversation on this topic, but it seems to me that most people think about geometry as a difficult subject, but instead we use geometry in everyday life although are unaware of that fact. - like cutting the food for example. :-)

CityVP Manjit

prije 7 godina #27

Mamen 🐝 Delgado

prije 7 godina #26

😘

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #25

You’re wright, Lisa Gallagher To understand nature around us, like rock formation, we use also geometry. I think that within each one of us lurks a small geometrician. :-) Thank you for your kind words of praise.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #24

I'm so glad you like it, Mamen Delgado. By the way, dear Madam Ambassador, I like your new picture. :-) Thanks for your support.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #23

#24 Thank you for the share and comment my dear Madam Ambassador. :-)

Lisa Gallagher

prije 7 godina #22

Mamen 🐝 Delgado

prije 7 godina #21

Lisa Gallagher

prije 7 godina #20

Lisa Gallagher

prije 7 godina #19

Lisa Gallagher

prije 7 godina #18

I'm going to be honest Lada Prkic, math was never my strong point. I dont remember Geometry.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #17

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #16

Exchanging thoughts with a thinker like you, Ali Anani, also send my mind into new territories. I'm grateful for such an opportunity.

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #15

Lada Prkic- thank you so much for the link and I never expected that imagining the human behavior as a fractal would send my mind into new territories.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #14

Dear Debasish, your comments sound like your beautiful poems. Math, geometry, and poetry have much in common. Inspiration and imagination are needed in poetry as well as in geometry and mathematics. Many poets have also been mathematicians. "Pure mathematics is, in its way, the poetry of logical ideas." So, you are a mathematician, in a way, but you are not aware of that. :-)

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #13

Many thanks for your comment Ali Anani. I’m so glad that you like the visuals, which are an essential part of this buzz. As I said at the beginning of the post, I prefer visualization wherever possible because I am pretty much a visual learner. While I was writing this buzz I was also doing some research on post topic and came across an interesting article dealing with a statement that human behaviour follow the same fractal patterns which are the building blocks—atoms--of the natural world. This applies not only to the physical world, but also to the world of human emotion and behaviour. Hence human behaviour is fractal in nature. An eye-opening article worth reading, https://onefootwalking.wordpress.com/2011/01/29/fractals-and-human-behavior/ Yes, we are, indeed, fractals of behaviours.

Ali Anani

prije 7 godina #12

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #11

Praveen, I think your comment about bubbles inside bubbles is just the right cue for a comment of our friend Ali Anani.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #10

Praven, I think your comment about bubbles inside bubbles is just the right cue for a comment of our friend Ali Ali Anani.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #9

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #8

“Fractality” is only one of the Platonic solids amazing properties. To me, the nesting of the Platonic solids one inside the other is the most intriguing feature. This video simply thrilled me. Thanks for mentioning the effort, dear Praveen Raj Gullepalli. I have to say that I really enjoyed writing this post. I made it without haste and wrote only when I was in a writing mood.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #7

Thanks for the share, Aurorasa.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #6

Dean Owen, I sincerely appreciate your kind words about my buzz. While I was preparing the post I came across a lot of sites on how to build models of the Platonic solids using sheets of paper or other materials. It’s really interesting for the kids like me. :-) By the way, all these solid names seem so mystical and I like how they sound.

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #5

Excellent modification of the famous quote, Ken. Love, like music, has its own geometry. Everything is interconnected. :-)

Lada 🏡 Prkic

prije 7 godina #4

Thanks Gert! I put a lot of efforts into this buzz. Sadly, some editing options are not displayed as in the draft.

Dean Owen

prije 7 godina #3

Ken Boddie

prije 7 godina #2

Gert Scholtz

prije 7 godina #1